Our History

our history

Almost 150 years ago, one man’s spirit of adventure took him to India. There, the future course of his life was set in motion. He saw the appalling living conditions and the social isolation of people with leprosy. His compassion and action birthed The Leprosy Mission, an organisation that now works to bring healing, inclusion and dignity to leprosy-affected people around the world.

-

1870s

The early years

In 1869, Wellesley Bailey, a young Irishman, sets sail for India hoping to find a career there. While training to be a teacher he sees for the first time the devastating effects of leprosy. Describing this moment he writes later ‘if there was ever a Christ-like work in the world, it was to go amongst these poor sufferers and bring them the consolation of the gospel.’ There was, at the time, no known cure for leprosy, and the bacillus that causes the disease was not identified until 1874.

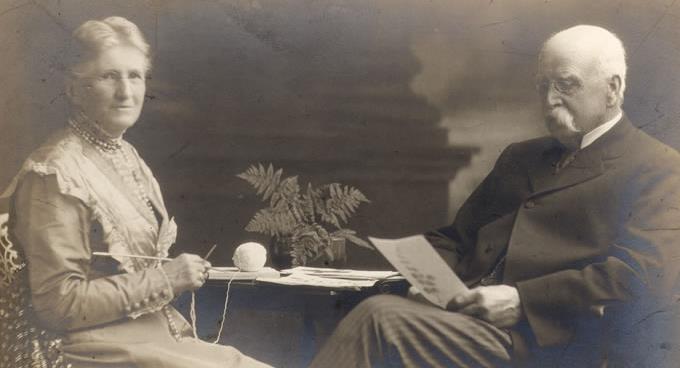

In 1873 Wellesley and his wife, Alice, return to Ireland and begin telling people about the needs of people with leprosy. And in 1874 `The Mission to Lepers’, now The Leprosy Mission, is born when Charlotte Pim and other friends of the Baileys promise to raise £30 a year to help leprosy sufferers in India. In the first year £600 is raised. By the late 1870s the Mission was caring for 100 leprosy-affected people in north India. Wellesley Bailey is appointed the first secretary, based in India.

-

1880s and 90s

India and beyond

The Mission gave grants primarily to other mission organisations, encouraging them to care for people affected by leprosy, and starts to open its own homes and hospitals – sometimes called ‘asylums’ in those days – where needed. Mary Reed is sent to Chandag, north India, as the Mission’s first missionary worker. Most financial support initially came from Ireland and Scotland, but support offices started to be formed in England, and the first public meeting in London raised almost enough money to build a leprosy home and children’s home.

Alice Bailey’s health deteriorated and the Baileys returned to the UK to be based there, but continued to travel extensively in India and beyond to see the needs of leprosy-affected people and to encourage mission organisations, local government officers and donors to engage in the work. Wellesley Bailey visits Mandalay, in what was then Burma, to open the first ‘Mission to Lepers’ home outside India. He also toured the USA and Canada and a support office in Ontario was formed.

Leprosy-affected people remained segregated from the rest of society. Many lived in asylums or hospitals, like the ones supported by TLM, with loving care but no hope of a cure.

-

1900s and 1910s

Into Africa

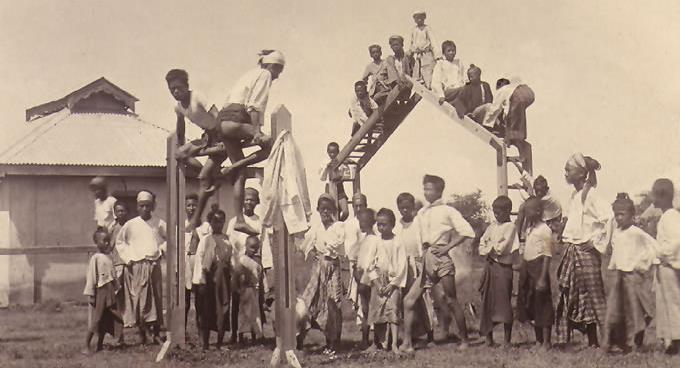

Gradually the Mission’s work extended to China and Japan. Work then began in Africa. Income for, and interest in, the Mission’s work steadily increased throughout these decades. Wellesley Bailey and his wife travelled to China, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore and India, visiting projects, raising awareness of leprosy and asking for support. Governments began to contribute to the costs of the Mission’s homes.

By the time Wellesley Bailey retired in 1917 the Mission had 87 programmes in 12 countries with support offices in eight countries. The annual income had risen from £5,000 to £40,000. William Anderson succeeded Wellesley Bailey as secretary of the Mission.

-

1920s and 30s

Consolidation

The Leprosy Mission was well-connected through the first leprosy congresses to the slowly growing body of knowledge on the disease. It started early experiments with treatment using chaulmoogra oil: injections were painful and only a few were cured, but the very possibility of cure saw the banning of the word ‘asylum’, replaced by ‘hospital’. Once only able to offer refuge and a long-term caring home, TLM began to develop into a medical mission. Under Anderson’s leadership the Mission added a further aim to its vision statement: to aid in the attempt to eradicate leprosy.

The headquarters moved from Dublin to London. From the end of the 1930s much of the Mission’s work was affected by the Second World War, particularly in China, Japan and Burma. Many patients were dispersed and hospitals overrun. William Anderson retired in 1942 and Donald Miller became the new general secretary of the Mission.

-

1940s and 50s

Treatment and surgery

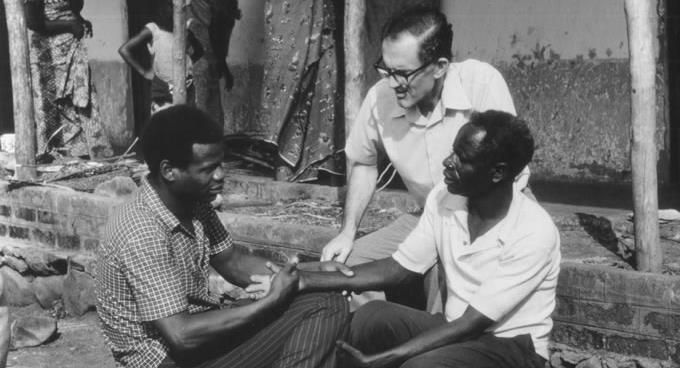

Mission doctors in Nigeria and India began experimenting with a new anti-leprosy drug, dapsone. It became the first effective cure, especially for the less virulent form of leprosy, and sent many patients home symptom free. This revolutionised leprosy work. Over the following 15 years millions of patients were successfully treated and the former leprosy homes – no longer relevant – were closed.

Dr Paul Brand, a surgeon, and colleagues at Karigiri, South India, pioneered life-changing reconstructive surgery to correct leprosy-related disabilities. Wilfred Russell, the next General Secretary of the Mission, visited Korea and agreed to support a new hospital there. A TLM hospital was opened in Nepal and work extended into Bhutan.

-

1960s and 70s

Expansion and community

In 1965 The Mission to Lepers changed its name to The Leprosy Mission (TLM) to avoid the negative connotations of the word ‘leper’. Newberry Fox took over as General Secretary. The Mission started projects in Papua New Guinea, and supporters in Australia and New Zealand began to fund work in Thailand and Indonesia. ‘Survey, education and treatment’ programmes dramatically increased TLM’s outpatient work. Skilled local paramedical staff travelled from village to village diagnosing new cases of leprosy, providing new patients with anti-leprosy drugs and keeping records of all patients.

By 1974, The Leprosy Mission’s centenary year, TLM had 30 of its own hospitals and leprosy centres, most of them in India. In India alone, it is reported that places were available in TLM hospitals for 10,000 inpatients, and in the villages and out-patients clinics more than 124,000 were receiving treatment. It also supported 90 different Christian societies and missions working in more than 30 countries, including 14 in Africa. TLM adopted a new global structure with national councils providing financial, prayer and personnel support to enable the newly established TLM International to direct field operations in South Asia, Southeast Asia and Africa through a regional structure.

15 million people in the world were still suffering from leprosy, and only one in five was having any sort of treatment. Some patients were beginning to develop resistance to dapsone, and researchers worked to discover new drugs that will be effective against leprosy. TLM became a founding member of ILEP, the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations.

-

1980s and 90s

Breakthrough in cure and care after cure

In 1981 the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended a new combination drug treatment for leprosy – Multi-Drug Therapy (MDT). People were cured in as little as six months. In its international conference in 1982, TLM adopted MDT in its treatment of leprosy and agreed an international budget of £5 million. MDT programmes were implemented, involving a major deployment of staff and finance, and the results were dramatically effective.

As more leprosy-affected people were released from treatment, caring for people with lasting disabilities became increasingly important. From the late 1980s, under the theme ‘care after cure’, The Leprosy Mission rapidly increased its programme of social, economic and physical rehabilitation. New projects focused on training, the formation of self-help and self-care groups, community inclusion, and the development of livelihoods for leprosy-affected people. Eddie Askew, Bill Edgar and Trevor Durston were TLM’s General Directors during these decades.

-

2000 to 2024

Staying focused

‘Together we serve’ (1998) is the Mission’s first genuinely global strategy. Its successor in 2005 adopted the vision ‘A world without leprosy’ and the goal ‘to eradicate the causes and consequences of leprosy.’ TLM’s core priority remains leprosy, with the understanding that this will naturally encompass other physical disabilities and other excluded people, especially where this enables contact with communities. New sets of values are adopted, led by the words ‘to be like Jesus’ and ‘because we follow Jesus’.

The Leprosy Mission International adopted a new constitution in 2001, with a governing Board of Trustees. With Geoff Warne as new General Director, the decision was made in 2011 to move away from the centrally-directed, regional structure and reformulate TLM as a more decentralised Global Fellowship of Member Countries, who signed the TLM Charter. Half are ‘supporting’ countries (mostly in the Global North) and the other half are ‘implementing’ leprosy programmes within leprosy endemic countries.

By 2010, new leprosy case numbers were down to 250,000 or less per year, from a peak of more than 1 million, but there was concern that there were many hidden cases and a huge reservoir of people disabled or at risk. Advocacy programmes were introduced focusing on human rights and community inclusion. TLM is a member of an increasing number of global forums all enabling it to express a voice for leprosy. Brent Morgan took over as International Director in 2016 with the intention of boosting global revenues which, at around £20 million per year, have been almost static for a decade.

In 2019, The Leprosy Mission’s global strategy put more focus on stopping transmission, and our programmatic, research and fundraising partnerships increased. Our fundraising aim was to be raising £40million per year by 2023.

The Covid pandemic proved a setback in the fight to defeat leprosy. A series of extended national lockdowns across a number of leprosy endemic countries meant that active case finding initiatives did not take place and patients were not able to reach medical centres. As a consequence, the number of people who were diagnosed and treated for leprosy fell by a third during 2020 and 2021. The pandemic also left the most vulnerable even more exposed to poverty and hunger.

-

2024 onwards

The Leprosy Mission starts its 150th year in the shadow of the pandemic, knowing that there is ground to be made up in the effort to find and diagnose all leprosy cases. Despite the setback of the pandemic, The Leprosy Mission has committed to an aspirational goal of zero leprosy transmission by 2035. This is possible because of the new tools that are available and those that are under development. Among these tools is post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), which in the context of leprosy is an antibiotic treatment that can prevent people from developing leprosy after they have been exposed to it. When combined with contact tracing and active case finding, PEP has been shown to significantly reduce leprosy transmission.

In the years to come, further tools are expected to become available, including revolutionary diagnostic tests and even a leprosy vaccine. In the 2020s, we have all the tools we need to end leprosy for good – the only things we lack are resources and political commitment.

As The Leprosy Mission marks 150 years since its founding, the finishing line in the fight to end leprosy transmission is within sight. However, The Leprosy Mission’s work will not be limited to ending leprosy transmission. The years to come will see us work alongside Organisations of Persons Affected by Leprosy even more than we have before, to support people with leprosy related disabilities and to tackle leprosy related stigma.

Even when we have stopped leprosy transmission, our work will still not be finished. For as long as persons affected by leprosy are living with disability and stigma because of the disease, we will offer support.

The persons affected by leprosy that Wellesley Bailey met 150 years ago were considered total outcasts, forced to live on the outskirts of communities with no hope of a cure. Today, a cure for leprosy exists and persons affected by leprosy are influential advocates, speaking to local and national governments and representing their communities at the United Nations (see photo above of Ivonia from Timor Leste at the UN HQ in New York).

Whilst challenges still exist, the future has never been brighter. With the right investment, we can be the generation to beat leprosy.